Tracking Success with Metrics

In my first year out of college I decided it would be really great if I got into shape. And I forget how I came across the Insanity workout series, which is similar to P90X if you've heard of that. Now with Insanity, they give you a two-month calendar, and throughout the two months you do a series of fitness tests where you get one minute to do as many reps as you can of eight different exercises.

And this is really useful because you can see that number go up over time. Even though this was a few years ago, I still have my sheet so I can see that I improved on all the exercises. It's good to have this kind of numerical indicator of your progress. I think this was really smart of them to include this in the series, because numbers do not lie (most of the time). I can see that I got better.

Now what does exercising have to do with chess? Well today we're going to talk about the role numbers and metrics can play in the learning process and how we can use these in chess.

Last week I talked about how it's great to get some kind of record of a baseline performance. Where are you now, at the beginning of your journey? And the example I showed was more of a visual example. What do I look like playing chess. What is my thought process like? What mistakes do I make? I can see these things in the videos as I watch them. I compared this to taking a "before" picture when you go on a diet. Once you have the "after" picture, you can really compare results and see the improvements.

But this sort of visual indicator is only one side of the story, because it's very subjective. It might be more visceral to look at something. And this might, in fact, be the best form of evaluation for a lot of skills. But numerical measurements or metrics are also a very important tool you can use, and there are at least three great ways we can use metrics.

First, metrics can serve the same purpose as a "before/after" visualization. You can take a metric at your starting point, and then gather that same metric at the end of your journey. And you can see in a concrete, measurable, way how you've improved. For a lot of people in a lot of cases, this is better proof of success. If you're trying to get something done in a business, for example, you need to have measurements to prove that things have gotten better. So if you're more logically minded, then metrics are an even better way to show the difference of what you've accomplished.

Another way metrics typically beat visualization is that they give you a better idea of incremental change and intermediate progress. If you're thinking about changes you can observe, see or hear, these might not change much from day to day. You might not be able to tell the difference if the song you're playing sounded better today versus the day before. You might make some big progress early and then seem to plateau for a while. It's only in the accumulation of these changes over a long period of time that the difference becomes readily apparent.

When you have a concrete metric, incremental changes are more noticeable. Trends are more noticeable. You could only do 10 reps of an exercise before. And maybe now you can do 12 or 13. That's not such a big change that you'll notice it in your body shape, but you measure it, and you know you're improving.

Another benefit to metrics is that they can make your weaknesses much more clear. If you're able to gather different data on different areas of your skill, you might see that one area is progressing while another is not. Maybe you're able to do a lot more pull-ups than you could before but you can't actually do more squats. That way you know, you'd better stop skipping leg day.

Or for a dieting example, if your weight has gone down but your body fat percentage is staying the same, this might mean you've reduced your portions but you're not actually eating healthier food. (Maybe. I'm not a nutritionist so don't take anything I say about too literally on that subject).

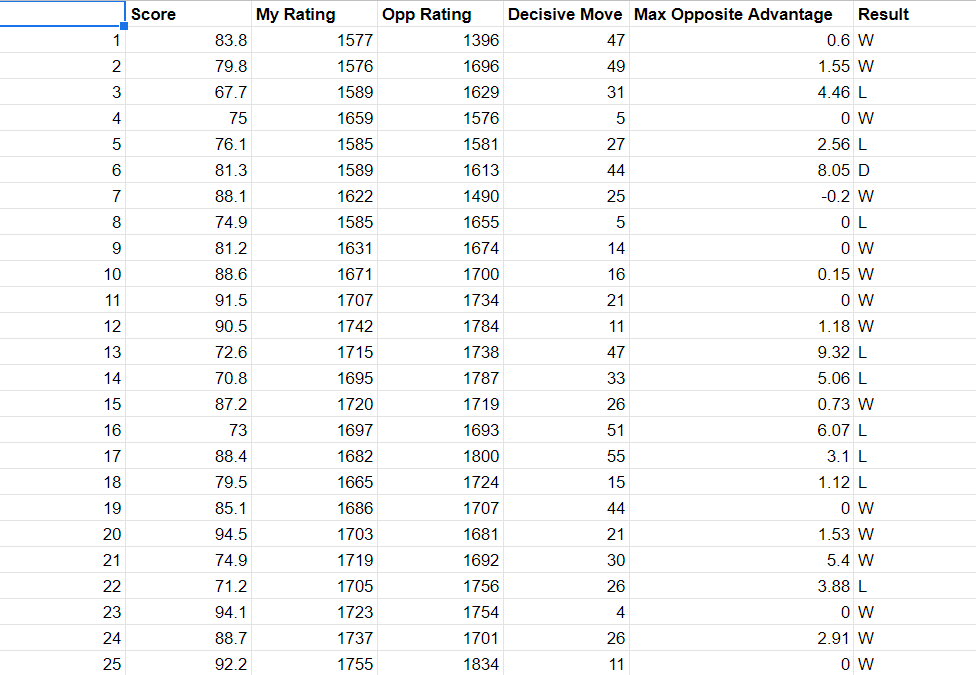

Now let me show how I applied these ideas to my chess metrics. I made a spreadsheet to track a number of different value after each of the games I played.

The metric that's really the core metric whenever we're talking about chess performance is your rating. Chess is really nice in that it's pretty much universally accepted that any competitive chess network will use an ELO rating system that just gives you a number that represents how good you are. So while it would be great to see a video of myself having a clearer thought process, when it comes to "proving" to other chess players that I've gotten better, rating is the thing I would need to use. So I'm tracking my rating after each game as well as my opponent's rating. If I get better I expect my rating will improve over time, as well as the ratings of my opponents. My ultimate goal, when I set that, will be a rating-based objective.

But rating doesn't necessarily tell the whole story. It will have some incremental improvements that I can track, but another number that Chess.com allows me to track is Accuracy (or score). Sometimes, whether you win or lose can be affected by a single mistake, or by running out of time, which I do kind of a lot. But accuracy measures your performance in a way that isn't quite as swayed by these things. So taking a rolling average of accuracy can give me an idea of incremental improvement even if my rating isn't budging.

Finally, I have a couple fields that are geared towards helping me identify specific weaknesses. The "Decisive Move" column is where I record the move where the game was really won or lost. This can potentially show me if I'm losing games in the opening more, or in the endgame.

I also have the "max opposite advantage". The chess engine can evaluate every position as "good for white" or "good for black". So in this column I record the largest advantage held by the player that didn't win. And I can see from this column that in a lot of my losses, I actually had a large advantage at some point. This tells me I'm usually getting an advantage, but I have to convert my advantages better, or identify key areas in the game.

One metric I wish I had recorded was something related to the number of times I used more than a minute on a single move. Using too much time was a big deal for me; I lost several games because my clock was running low. So having a measurement of this would be good.

Periodically I'm going to do more checkpoints. I'll play more games and figure out where these numbers are so I can do comparisons. And I'll probably come up with more numbers to identify more weak points.

Now of course, metrics are just one piece of the puzzle. There are a lot of skills that are difficult to quantify, and so as I continue to explore how to learn I'm gonna try to come up with better ways to handle these to accomplish all these goals we talked about here. If you want to get a higher level overview of the main principles in learning right now, and you don't want to wait for more articles, you should download my free Learning Checklist. Thanks for reading, and I'll catch you next week!

Here's this article in video form: